Most academics are paid to do research. Research is part of your job description. Research figures prominently in the criteria for hiring, tenure/confirmation, and promotion.

This can feel out of sync with the reality of your daily life in the university. You teach. You attend meetings. You do the work necessary to do those 2 things well. You are available for meetings with individual students. You might supervise graduate students. Department meetings rarely talk about research, making it seem like some kind of personal thing.

Research can feel like it’s a hobby.

You do it in your “spare time” and during “vacations”. If you schedule time regularly to work on your scholarship, it frequently gets shifted, or dropped, when other things come up.

You enjoy your research, or you did once. You work on questions that are of interest to you. If you think about it too hard, it seems crazy that anyone would pay you to read those books. Surely real work should be at least a little bit hard or unpleasant? Maybe you even secretly sabotage your research to make it feel more like work.

What makes something a hobby?

I’m making a quilt. I bought the fabric several months ago. This weekend I got out the fabric. Looked at the plan I had. Cut out squares. Sewed things together.

The purpose of making the quilt is the enjoyment I get out of the process.

I enjoy selecting colours and fabrics. I enjoy the process of cutting out squares, sewing them together, and arranging them in a pleasing pattern. I enjoy the process of seeing these fabrics become something different through this process.

Sewing a quilt, for me, is like watching movies, or reading books, or skiing.

I happen to get a product out of it. And that product can meet other needs — giving this quilt to my parents will contribute to my relationship with them. I could even sell the product and meet my need for cash to fund my hobby.

It passes the time. It is relaxing. It works a different part of my brain in a different way. The process meets my needs for creativity. It helps me relax.

A hobby only meets these personal needs.

It is valuable as a hobby, even if I finish the quilt top and never put it together with the batting and backing and make it into something that can be used to keep someone warm. I can put half-finished quilts away for months (or years), and bring them out later and the benefits of quilting to me are not diminished.

Your research may share some aspects of this hobby of mine. You may enjoy it. It may satisfy your need for creativity or some other need.

Just as I select the quilting project, you may select the research topic and focus. You may do this primarily based on your own curiosity and interest. And satisfying that curiosity is a need that will be met whether you devote time every week to working on your project, or whether you leave it for long stretches and come back to it.

As a hobby, your research will meet your needs whether you ever share your findings with anyone else, at a conference, in a publication, or in the classroom.

What makes something a job?

What makes something a job?

The simple answer is that you are paid to do it. But that begs the question, why are you paid to do research?

You are paid to do research because it has value to someone else. That value might not be immediately obvious. But no one pays you to do a hobby.

Even if someone pays me to make them a quilt, it is not because making quilts makes me happy. If someone pays me to make a quilt, they value the warmth, the beauty, the joy the quilt brings them. It is those things that determine the price of my quilt.

Enjoyment doesn’t make research a hobby. Nor does struggling make it not a hobby. The key factor that distinguishes a hobby from a job is the value your work provides to someone else.

If you move on from your research before it is useful to someone else, you are not doing your job. You are treating your research as a hobby.

What do you do to ensure the value of your research is realized?

If you believe that teaching in higher education requires teachers to be active scholars, what are you doing to ensure that you are an active scholar and that your scholarship has an impact on your teaching?

If you believe that your research could make an important contribution to scholarly debates in your field, or could change the way other researchers approach this topic, what are you doing to ensure that other scholars in your field know about your research?

If you believe that your research is important to the practice of a particular profession, what are you doing to ensure that those professionals know about your findings and are able to integrate them into their practice?

If you believe that your research is important to how particular organizations (commercial or charitable) deliver their products or services, what are you doing to ensure that those organizations can benefit from your research?

If you believe that your research is part of what makes your university great, what are you doing to enhance the profile of your research and your university?

…

If you believe any of those things, are you giving your research and scholarship appropriate priority when you are planning how you use your time? And is it clear to those around you how your research contributes to your collective goals?

P.S. BTW, that quilt got finished and lives on the back of my parent’s sofa.

Related Posts:

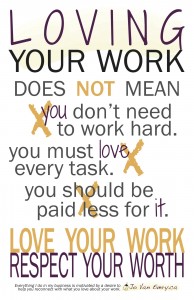

Lies you’ve been told about loving your work

Communication vs Validation: why are you publishing?

The relationship between writing for scholarly audiences & for wider audiences

Are you treating writing as real work?

This post was edited April 12, 2016; links update 23 April 2020. Edited Sept 2025.

Great post, so true! am already chasing up leads which I should’ve done ages ago – thanks!

This is a really smart and helpful post, Jo–and I don’t say that just because I do a little quilting on the side too! It helped me think about the answer to the question I was recently asking on my own blog about when reading is (or isn’t) research. It’s true that almost any reading may contribute to my own learning and intellectual growth. The key issue in terms of whether it is professionally significant reading is whether it contributes also to someone else’s learning and intellectual growth–whether, as you put it, it provides value to someone else. It might do that through my teaching or through my writing and publishing, but what matters is that the reading develops into something outward-directed.

I suppose the issue still remains that it isn’t always immediately clear whether we are doing work or pursuing our hobby if we are lucky enough to have a job that aligns closely with our values and interests. Sometimes we buy fabrics just to add them to our stash. But we do that because someday we may find the pattern or occasion for which they will be just right! Reading “for fun” is like that, I think, for someone in my job. I’m currently teaching a class on close reading and needed examples of different kinds of narrative voice as illustrations. Everything I needed was on my living room bookshelves: a little Ian McEwan, a little Hilary Mantel, a little Anne Tyler and Elizabeth Bowen and Virginia Woolf. And of course the new class I’m developing on Vera Brittain et al. is a stronger example–and the papers on Soueif too. You have to allow yourself to collect material you like even if you aren’t sure how you’ll be able to use it. The point is, you expect to use it, and now that you have it, you’ll keep thinking about how and when.