This is a guest post by Sarah Burton, a Leverhulme Early Career Research Fellow. You can follow her on Twitter @DrFloraPoste. I’ve added the headings, a few comments (in italics at the end), and the related posts.

Thinking about what the life of an academic would look like I usually pictured piles of leather-bound books atop a mahogany bureau, writing by the subtle glow of a desk lamp, and long hours of reading in a sumptuous comfy chair. In practice, not a lot of this turns out to be accurate. Reading – something that should be the staple of academic research – is brutally hard to make space for amid the numerous other responsibilities of an academic post. At around six months into my current post – a Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship – I decided that reading had to stop being the thing I fit around other work. Having not had the time to read extensively during the final year of my thesis, and then a year as a Teaching Fellow, I’ve started to feel increasingly dislocated from the practical elements of being creative, making ideas, and pushing myself forwards intellectually. More than that, absorbing myself in reading – fiction, poetry, memoirs, academic, journalism, essays – makes me a better writer, and so much more adept at articulating my thoughts.

Wanting to make reading the ice sculpture that my research party revolves around, I set up a 3-month reading plan that attempted to secure this as a daily activity. Most of all, I needed a plan that demonstrated to me how allowing myself to make reading my focus would support everything else I want and need to do.

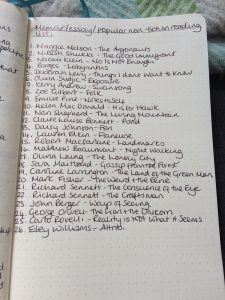

What I tried to do with this is to show myself how reading would be productive and intellectually energising – that it would set me up for fieldwork and major publishing opportunities. In doing this, I was very aware that time needs to be set aside for doing job-like and mundane work around events organising and other administrative tasks, and to be doing this in such a way that it doesn’t intrude on reading time. Just the act of making the 3-month plan is my attempt to assert reading as a legitimate and valid part of academic labour. I also wanted to be very structured about the type of reading I did – making sure to include academic texts, popular non-fiction, essay writing, and memoirs, so that I would be making progress in multiple strands of research and stretching my figurative writing and thinking muscles.

Breaking the plan down to daily tasks

My next move was to set up some short, medium, and long-term goals and to set out an ‘ideal’ structure for a day of reading – to prevent me pottering around the activity and consequently doing nothing much of note. So far, in practice, this is not working out. Thanks to various other commitments, travel, and the timing of the symposia I’m organising, I’ve not been successful in sticking to these ideals – which, itself, scuttles my larger attempts at privileging reading.

What I am doing well is on my monthly activities:

It’s been easy to consistently write my research diary for both reading and my language practice – and it’s been fascinating how these have intersected. Writing feels so much more like a legitimately work-related practice and, in some respects, I’m a little worried that I find this so much easier to incorporate into my working day, and that I get much more of a sense of achievement from it than from reading. For me, there’s still much to be done personally in terms of genuinely believing that reading is work.

The final thing I did was to create a reading list. Ticking things off a to-do list is catnip for me and it helps to see exactly what I want to achieve during the three months. Referring back to this list also helps me retain my excitement and enthusiasm for the work – the texts here aren’t straightforwardly academic and the idea that I get to focus on this sort of literature reminds me that the research project I’m doing is one that is stimulating, refreshing, and one that I care about.

Beyond the plan

Nevertheless, I’m continuing to find making space for reading a difficult prospect. There’s not much convincing necessary to want to make reading a more central part of academic work; on the other hand, what is difficult is convincing yourself that reading counts as work. Despite knowing that voracious and extensive reading makes for rich, subtle, and sensitive analysis in my research it still continues to be something that I struggle to do because it feels so closely associated with leisure and pleasure. Underscoring this is the constant and insistent presence and pressure of my inbox. Ros Gill (2009) has written so powerfully about the affective resonances of the ‘always on’ culture in our everyday lives and the ways this takes us over and compels us towards hyper-industrious work patterns. One of the biggest blockages in putting reading at the centre of my academic work is the unrelenting sense that lurking in my inbox are ever-proliferating requests, demands, and jobs that will only get more numerous and harder to do if I ignore them for longer than an hour. Encircling all of this is the ‘publish or perish’ mantra, incessantly branded into us from the beginning days of the PhD. The early days of research are necessarily slow and don’t produce much of material substance, but it’s difficult to remember this when the intense pressure to be always producing and publishing 4* REF-able research sits – quietly but insistently – with you daily.

My attempts to be accountable to myself serve both as encouragement but also, at times, reasons and ways to judge, punish, and shame myself. Gradually, it’s dawning on me that a practical strategy isn’t enough and what needs to be challenged is a mindset – inculcated from the all-consuming neoliberal university – that only authorises some forms of work. Doing this is a striking reminder of the extent to which I’ve been consumed by this ‘always on’ culture and the ways that I perpetuate it on myself – and very likely others, too.

Jo’s brief comments: I’m sure Sarah is not alone in finding it difficult to treat work that is enjoyable, and that one also does for leisure, as work. Her point about the pressure for visible outputs is also one shared by many. The imposition of shorter time frames for evaluating outputs on work which is, by its very nature, long term has created many of these difficulties. My work is focused on helping you navigate these contradictions.

Related posts:

When is Reading Research by Rohan Maitzen at Novel Readings.

What is Research? (in which I reflect on Rohan’s post in relation to some other things)

Juggling 101: elements of a good plan is more general. Sarah’s plan is a good illustration of both how to create a good plan and the difficulties of actually putting it into action.